Detailed Notes

Cultural and Traditional Differences Between Mising and Deori Communities of Assam

1. Historical Origin and Migration of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

The Mising community traces its ancestry to the Adi tribes of Arunachal Pradesh, believed to have migrated from the upper courses of the river valleys in Tibet or China around five centuries ago. They settled along the Brahmaputra riverbanks, adapting to a riverine lifestyle deeply connected with agriculture and fishing.

The Deori community, on the other hand, belongs to the Bodo-Kachari group of tribes. The name “Deori” is derived from Devagrihik, meaning “worshipper of gods.” Historically, they served as priests and temple caretakers, performing religious duties for the Chutiyas and other neighboring tribes. Their migration patterns placed them in eastern Assam and parts of Arunachal Pradesh.

2. Language and Communication of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

The Deori language is a Tibeto-Burman tongue. However, today, only the Dibongiya sub-group of the four Deori divisions (Dibangiya, Tengapania, Borgoyan, and Patorgoyan) actively speak it. Assamese is now widely used among the rest.

The Mising language, known as Plains Miri or Mising Ager, is a Tani language, also belonging to the Tibeto-Burman family. It shares similarities with Adi, Nyishi, and Apatani languages of Arunachal Pradesh. Mising continues to thrive as a spoken and written language, reflecting the community’s effort to preserve its linguistic identity.

3. Religion and Belief Systems of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Religion forms a key distinction between these two communities.

The Mising community primarily follows the Donyi-Polo faith, which revolves around the worship of the Sun (Donyi) and Moon (Polo) as symbols of truth and justice. They believe in various benevolent and malevolent spirits that influence natural and human life. Over time, a section of the Mising population has adopted Hinduism, blending indigenous practices with Assamese Vaishnavite customs.

In contrast, the Deori community traditionally practiced Hinduism mixed with animistic beliefs. Their rituals often honor deities such as Kundi-Mama (Hara-Gauri), and their priestly class conducts elaborate sacrifices and ceremonies at community shrines known as Sals. Some Deoris have also embraced Buddhism, yet their ancient ethnic worship remains an integral part of their heritage.

4. Cultural Practices and Festivals of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

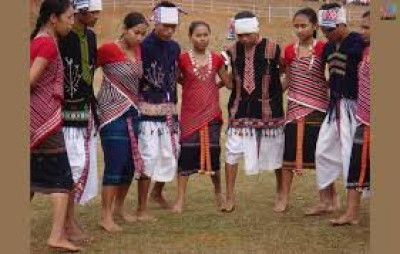

The Mising people are known for their colorful attire, music, and festivals that celebrate nature and unity. Their post-harvest festival, Porag, brings together entire villages for singing, dancing, and feasting with traditional rice beer (po:ro apong). Another notable celebration is Ali-Ai-Ligang, which marks the beginning of the agricultural season with traditional songs (Gumrag Soman) and community bonding.

The Deori community celebrates several unique festivals, including Bisu, a major spring festival held in mid-April to welcome the Assamese New Year. Other important religious events include Deo Puja and Swania Puja, which involve sacrifices, community prayers, and cultural performances that express gratitude to deities.

5. Dress and Handicrafts of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Mising women are skilled weavers, known for producing handwoven textiles with intricate geometric designs. Their traditional dress includes the ege (skirt), gasor (blouse), and seleng (shoulder cloth), often made using natural dyes. The handloom culture of the Misings is also a significant source of income and identity.

The Deori attire is simpler but elegant. Women wear the ekor, riha, and mekhela, often decorated with motifs inspired by religious symbols. Traditional jewelry made from silver and beads complements their cultural expression.

6. Livelihood and Economy of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

The Mising community primarily depends on farming and fishing, with rice, pulses, and vegetables forming their staple produce. Their proximity to rivers makes fishing a vital part of daily life. Mising households often rear poultry and pigs, and traditional rice beer (apong) plays a role in rituals and social gatherings.

The Deori community also engages in agriculture, cultivating paddy and seasonal crops. Historically, they served as priests in royal courts and temples, though today they have diversified into other professions, including government service and education.

7. Social Organization and Family of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Mising society follows a clan-based system, with decisions often made collectively by elders. Marriage within the same clan is forbidden. The community follows a more egalitarian structure, where both men and women play active roles in cultural and social affairs.

Deori society, however, has a structured religious hierarchy due to their priestly roots. Elders and religious heads like Bor Deori or Sarudeori hold significant authority in community rituals and decision-making.

8. Autonomy and Political Identity of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Both the Mising and Deori communities have sought cultural and administrative recognition.

The Mising Autonomous Council (MAC) functions under the Assam government, promoting education, culture, and development among the community. The Deori Autonomous Council (DAC) serves a similar purpose, ensuring socio-economic upliftment and cultural preservation.

9. Cuisine and Daily Life of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Mising cuisine is earthy and unique, featuring smoked meats, fermented fish (namsing), bamboo shoot dishes, and rice-based delicacies. The Deori cuisine shares similarities but includes a greater emphasis on vegetarian offerings during religious ceremonies.

10. Cultural Harmony in Assam of Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

Despite their differences, both the Mising and Deori communities play vital roles in shaping Assam’s cultural identity. Their festivals, music, and crafts contribute richly to the diversity that makes Assam a vibrant land of traditions.

Are Mising and Deoris Same in Assam?

No, the Mising and Deori communities are not the same. While both are major tribal groups of Assam, they differ in origin, language, religion, culture, and traditional practices.

-

Origin: Mising people migrated from Arunachal Pradesh, whereas Deoris are historically part of the Bodo-Kachari group of Assam.

-

Language: Mising speak a Tani language, whereas Deoris speak a Tibeto-Burman dialect, mainly retained by the Dibongiya group.

-

Religion: Mising follow Donyi-Polo (Sun and Moon worship) and some Hindu influences; Deoris follow Hinduism blended with animistic traditions.

-

Festivals and Culture: Mising are known for Ali-Ai-Ligang and Porag, celebrating harvests and riverine life, while Deoris observe Bisu, Deo Puja, and Sawnia Puja, reflecting their priestly heritage.

Despite these differences, both communities contribute significantly to Assam’s cultural diversity and coexist peacefully in the region.

FAQs with Short Answers on Mising vs Deori Communities of Assam

-

Who are the Mising and Deori communities?They are two prominent tribal groups in Assam with distinct cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

-

What is the main difference between Mising and Deori origin?Mising people migrated from Arunachal Pradesh, while Deoris belong to the Bodo-Kachari group of Assam.

-

What languages do they speak?Mising speak a Tani language; Deoris use a Tibeto-Burman dialect, mainly by the Dibongiya group.

-

Which religion do they follow?Mising follow Donyi-Polo, while Deoris follow Hinduism with ancient ethnic practices.

-

What is the main festival of the Mising community?Ali-Ai-Ligang and Porag are major Mising festivals.

-

What are the major festivals of the Deori community?Bisu, Deo Puja, and Sawnia Puja are key festivals.

-

What is the main occupation of both groups?Both are primarily agricultural, with fishing common among the Mising.

-

Do both communities have autonomous councils?Yes, both have separate autonomous councils in Assam.

-

How are their attires different?Mising attires are more colorful with intricate patterns, while Deori attire is simple and symbolic.

-

Do the Mising and Deori communities interact socially?Yes, they coexist peacefully, sharing markets, schools, and regional festivals.