Ahom Dynasty History: The 600-Year Empire That Shaped Assam

Introduction: The Kingdom That Lasted Six Centuries

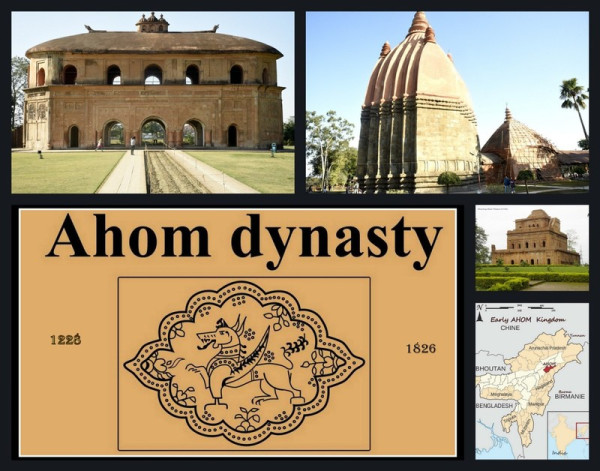

The Ahom Dynasty was one of the longest-ruling dynasties in South Asia, governing the Brahmaputra Valley of present-day Assam from 1228 to 1826. Founded by a Tai-Shan prince, the Ahoms created a powerful and resilient kingdom that successfully resisted Mughal expansion and developed a distinctive political, military, and cultural system. Their nearly 600-year rule profoundly shaped the identity, society, and heritage of Assam.

Foundation of the Ahom Kingdom

The Ahom kingdom was established in 1228 by Chaolung Sukaphaa, a Tai prince from Mong Mao in present-day Yunnan, China. Crossing the Patkai mountains with around 9,000 followers, Sukaphaa entered the Brahmaputra Valley and laid the foundation of a new state. His first capital was established at Charaideo near present-day Sibsagar.

Sukaphaa adopted a policy of peaceful settlement and integration. Instead of immediate conquest, he encouraged wet-rice cultivation, land development, and intermarriage with local communities such as the Bodo, Kachari, and other indigenous groups. This gradual process of assimilation is often described as Ahomization, where local tribes were incorporated into the Ahom political and social structure.

According to Ahom tradition, Sukaphaa was a descendant of Khunlung, the grandson of the heavenly king Leungdon. In reverence to his status, he was honored with the title Chaolung, meaning great lord.

Political Structure and Administration

The Ahom political system was highly organized and efficient. The king was known as the Swargadeo, meaning Lord of Heaven. The royal office was reserved exclusively for the descendants of Sukaphaa. However, the king could only be appointed with the approval of the Patra Mantris, a council of powerful ministers that included the Burhagohain, Borgohain, and later the Borpatrogohain. In certain periods during the 14th century, no king was appointed because suitable candidates were not found.

Ahom kings traditionally assumed an Ahom name ending in Pha, meaning lord. Later, many adopted Hindu names ending in Singha. For example, Susengphaa took the name Pratap Singha and was also popularly known as Burha Roja, meaning Old King.

The administration was supported by an innovative Paik system. Under this system, every able-bodied adult male, known as a paik, had to render service to the state in rotation. This service included agricultural work, military duty, construction of embankments, tanks, and roads. The system ensured economic stability and military preparedness without maintaining a large paid standing army.

The kingdom was divided into professional units known as khels, responsible for specific occupations such as boat-building, blacksmithing, weaving, and agriculture. Provinces and administrative divisions were governed by officials such as Phukans and Baruas. Royal tours and inspections reinforced central authority.

The Ahoms also maintained detailed chronicles called Buranjis. Written first in the Ahom language and later in Assamese, these records documented wars, treaties, genealogies, famines, and political developments. Today, the Buranjis are invaluable sources for understanding medieval Assamese history.

Territorial Expansion and Key Rulers

Among the most significant rulers was Suhungmung, also known as Dihingia Raja, who ruled from 1497 to 1539. He expanded the kingdom westward, incorporated non-Ahom populations, and strengthened administration. The capital was shifted to Garhgaon during his reign.

Another key phase began under Supaatphaa, who established the Tungkhugia line of kings. This line ruled during the political and cultural zenith of the kingdom.

The kingdom reached its peak under Rudra Singha (1696-1714), who promoted administrative reforms, military strength, and cultural patronage.

Ahom Queens and Royal Authority

Ahom queens, known as Kunworis, played significant political roles. They were ranked in positions such as Bor Kuwori, Parvatia Kuwori, Raidangia Kuwori, and Tamuli Kuwori. Some queens were granted estates managed by state officials.

During the reign of Siba Singha (1714-1744), royal authority was symbolically transferred to his queens Phuleshwari Kunwori, Ambika Kunwori, and Anadari Kunwori, who ruled in succession and were called Bor-Rojaa. Certain queens, including Pakhori Gabhoru and Kuranganayani, maintained influence even after the death or removal of their husbands.

Military Strength and the Battle of Saraighat

The Ahoms are particularly remembered for their successful resistance against the Mughal Empire. The most famous confrontation was the Battle of Saraighat in 1671. Under the leadership of Lachit Borphukan, the Ahom navy defeated the Mughal forces led by Raja Ram Singh.

The Ahom military combined infantry, riverine naval forces, and guerrilla tactics suited to the geography of the Brahmaputra Valley. Natural barriers such as rivers and marshes were strategically used for defense.

Lachit Borphukan became a symbol of patriotism. His famous declaration, Dekhot ke Mumai dangor nohoi, meaning My uncle is not greater than my motherland, continues to inspire Assamese pride. He is commemorated annually during Lachit Divas.

Religion, Society, and Cultural Synthesis

The Ahoms originally practiced Tai animism with ancestor worship conducted by priests such as the Deodhai and Mohseng. Over time, especially between the 16th and 18th centuries, they gradually adopted Hinduism, particularly Shaivism and Shaktism. Vaishnavism, introduced by the reformer Sankardev, also became influential through the satra institutions.

Despite adopting Hindu practices, the Ahoms retained elements of their original traditions, creating a syncretic religious culture.

The economy was primarily agrarian, based on wet-rice cultivation in the fertile plains of the Brahmaputra Valley. The state promoted irrigation, embankment construction, and land reclamation. Trade included rice, oil, cotton, salt, and forest products, with connections extending to Bengal and neighboring regions.

Architecturally, the Ahoms constructed impressive brick structures and water reservoirs. Notable monuments include Talatal Ghar, Kareng Ghar, and Rang Ghar, the latter considered one of Asia's earliest amphitheaters. Tanks, embankments, and temples built during their reign still stand in Upper Assam.

Decline and Fall of the Dynasty

By the late eighteenth century, internal conflicts, succession disputes, and administrative weaknesses began to erode central authority. The Moamoria Rebellion from 1769 to 1805 severely weakened the kingdom and exposed deep social divisions.

The final blow came with Burmese invasions between 1817 and 1826. Prolonged occupation devastated the region's economy and population. The First Anglo-Burmese War brought British intervention, and the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826 formally ended Ahom sovereignty. Assam was annexed by the British East India Company, concluding nearly six centuries of Ahom rule.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The Ahom Dynasty remains central to the history and identity of Assam. It was one of the few regional powers that successfully resisted Mughal domination. Its administrative innovations, especially the Paik system, demonstrate a unique model of statecraft adapted to a multi-ethnic floodplain society.

The Buranjis continue to provide rich historical documentation. Ahom-era architecture, festivals like Bihu, and enduring clan names reflect their lasting impact.

Modern Assam's cultural, linguistic, and political landscape still bears the imprint of the Ahom legacy. Their story is not just one of longevity but of adaptation, integration, and resilience across six centuries.